Frida Kahlo Story Viva la Vida

For Frida, her paintings were not a representation of dreams but a way to cope with the reality of life.

She told her story from her own point of view and through the pain and passion of her experiences.

Family

Frida Kahlo’s story begins on July 6, 1907, when she was born in Coyoacán, Mexico. She was the third daughter of Wilhelm Kahlo and Matilde Calderón.

Her father, who later changed his name to Guillermo, was a German immigrant of Hungarian descent who worked as a photographer and held a liberally inclined set of views. In contrast, her mother was a Mexican conservative deeply devoted to her Catholic faith.

During her childhood, Frida was drawn more closely to her father than her mother. Through this different type

of thinking, she developed animosity toward the Catholic Church and became more drawn to her father’s intellectual

pursuits of photography, reading, and painting.

Guillermo Kahlo’s success as a photographer landed him a job with the Mexican government and its leader,

Porfirio Díaz. The Díaz regime was characterized by its adherence to a Darwinian type of social philosophy centering

on the concept of “survival of the fittest”.

La Casa Azul

Early Years

The Blue House is the place where Frida Kahlo was born—and where she both lived and died. In this location, a

six-year-old Frida battled against polio and won the fight. The disease left the dark-skinned and slender girl with

a limp when she walked due to shrinking in her right leg, but it did not prevent her from developing a fierce character.

In her youth, she was involved in many physical activities, such as running, wrestling, and swimming, but she shone brightest in intellectual competitions, such as debate.

Eventually, her intellectual ability and competitive spirit led her to become one of only 35 girls accepted to the free, prestigious National Preparatory School.

During this period in Frida’s life, she became part of a group of intellectual bohemians called the “Cachuchas” (the “Caps”), named for the distinctive hats they wore.

Also during this time, Frida met her first love: Alejandro Gómez Arias. The couple would spend hours dissecting

books and making sense of their time period, which was defined by the Mexican Revolution.

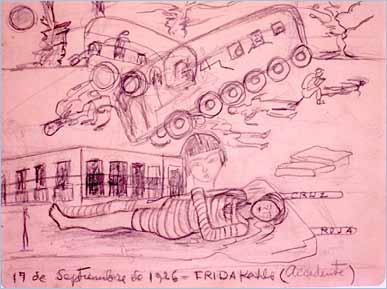

First Death

On one particular but seemingly normal day, Frida died for the first time: September 27, 1925. She and Arias boarded a

city bus toward Xochimilco when the vehicle crashed into a trolley and consequently into a street wall.

The accident itself was horrid. While the crash’s inertia propelled her into the air, the bus’s detached iron handrail

pierced the 18-year-old from the hip to the vagina.

The accident left her with several physical injuries, among them a broken pelvis, a broken back, dislocated feet,

and damage to her reproductive system. Aside from the apparent corporal loss, the accident condemned Frida to a sentence

of solitude as she was left immobilized in the process of partial recovery.

Frida’s state during this time was similar to the state of the country and even to that of the world: Mexico was in the aftermath of the revolution and in the hunt for a defining identity; likewise, the world was experiencing the consequences

of World War I.

Recovery

In recovery, given her physical limitations and her hampered emotional well-being, she found a new passion for painting.

She mostly painted herself because, as she described:

“I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.”

Art drew Frida closer to herself and to the muralist giant Diego Rivera. After her long rehabilitation and after she grew apart from Alejandro Arias, she began to socialize once again.

In contrast to Arias’s letters about a bourgeois lifestyle abroad, Frida began to resent the affluent members of society

and their idiosyncratic attitudes, preferring to think of herself as part of the peasant majority that embraced

pre-Columbian roots.

Further, there was a pervasive sentiment in Mexico at the time that drew idealists toward one another, and within one of the social groups formed by these individuals was the setting where Frida met Diego.

Diego Rivera

He was huge not only in size and stature but also in presence. He had been kicked out of the Soviet Union, but his affinity for communism did not fade; more than ever, he sought to incorporate it into the Mexican experience.

His mindset and belligerence drew Frida to him and eventually into marriage. Even after the numerous objections from her family—displeased by Diego’s morality, political ideology, and age (being 20 years Frida’s senior)—the couple settled in the Blue House. It began a turbulent relationship that lasted until her death years later.

“There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the train, the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.”

Frida and Diego went through a phase of mutual growth in which their artistic styles evolved. The Mexican government hired him to paint murals that depicted Mexican history. His themes shared the couple’s political ideals, and he would often paint Frida in them.

One of Rivera’s most significant murals, Ballad of the Revolution, portrays Frida as being in the middle of the

revolutionary fight and as the enabling figure who hands out rifles and other weapons to peasant soldiers. To Frida, the

revolution gave her a purpose in life, and she even changed her birth date to match the date of the start of the revolution:

July 7, 1910.

Ironically, the Mexican government began to fear communism after Diego had already completed many murals, and through his own

fear of prosecution, he was forced to look for work elsewhere.

The United States

In the wake of the Great Depression, Diego was hired by a commission in California, and the couple moved to the United States: the country that spoke the loudest in opposition to the communist movement, and in the middle of the “Red Scare”.

Frida’s experience in the U.S. was a mixed bag. On the one hand, she began to gain personal recognition for her art; on the other hand, she neither enjoyed life in the States nor with her husband.

For Frida, the U.S. represented the imperial capitalist society she stood against. She saw Americans as plain people, addicted to industrialism and competition.

In return, she felt—and was often treated—as an outsider, for her now famously characterized style of wearing colorful folkloric

dresses and having an outspoken, loud, and defiant personality.

Likewise, her personal life was branded by Diego’s habitual affairs with personal assistants, as well as by her own extramarital affairs with men and women alike.

Return to Mexico

On the bright side, her artistic career took flight from the inspiration these experiences provided. Her paintings began

to depict themes of loneliness, opposition, pre-Hispanic heritage, and naturalism.

Upon the couple’s return to Mexico, matters would only be an extension of their time in America. From the time Frida and Diego

married, her most igniting desire was to birth a little Diego—or “Dieguito,” as she would say—but the outcome of the bus accident

perpetually denied her this wish.

After several unwanted abortions, miscarriages, and pain, she reluctantly accepted the fact that she would never be able to be a

biological mother.

Thus, she became the adoptive mother of many species of animals—including monkeys, parrots, and even a baby deer—to try to make up

for the huge moral loss.

Adding to the aching times, Diego began to have an affair that hit too close to home: this time, it wasn’t an assistant or an unknown woman, but Frida’s own younger sister.

Frida allowed us to visualize the pain she endured when, in a therapeutic-like style of coping, she did what she knew how to do best: paint.

Her work took an even more gruesome turn than before—more blood, stabbings, hospital beds, skulls, and death, along with one painting in which she portrays herself as a mature woman and Diego as an immature young boy.

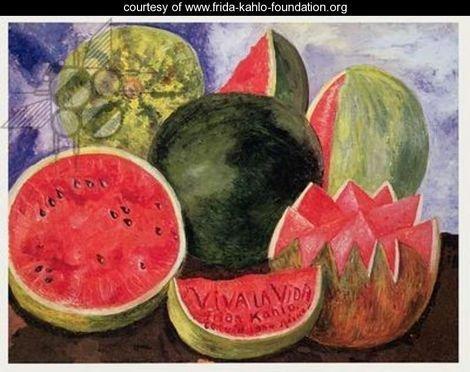

Final Days

Frida’s pain was obvious, and it took a significant toll on her health. She would medicate and drink away her sorrow, eventually deteriorating

her condition to the point that she developed gangrene in the right leg.

With the strength that characterized her, she pulled out of the hospital with an amputated leg and with a set of wings.

One of her last paintings included the words “Viva la Vida” next to her signature. In life, Frida’s days were counted after her release

from the hospital, but it is still unknown whether she planned this or not.

The last entry in her diary read: “I hope the exit is joyful and I hope never to return.” On July 13, 1954, at the age of 47, she was

found dead at the Blue House.

When Diego Rivera heard the news, he said he realized that the most wonderful part of his life had been his love for Frida. To date, it is still a mystery whether she died of natural causes or from committing suicide, but that debate cannot diminish the fact that Frida’s spirit never died.

Many people in history embrace the culture that defines them, but only a few are etched into it—Frida Kahlo is one of those individuals. In Mexican society, she represents folkloric joy, indigenous pre-Hispanic pride, the European immigrant dream, and

the revolutionary spirit.

Unable to be a mother, she adopted the environment as a whole—and over half a century later, this message of conservation resounds more strongly than ever: Frida did not belong to her time period, nor ours; she belongs to eternity.

¡¡Viva la Vida!! ¡¡Viva Frida!!

Frida Kahlo FAQ

Who was Frida Kahlo?

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) was a Mexican painter known for her self-portraits and for turning her own life—pain, love, identity, and politics—into bold, deeply personal art.

Why is the piece connected to “Viva la Vida”?

“Viva la Vida” appears on one of her last works (the watermelon painting) and is often read as an affirmation—celebrating life even when the body hurts, and reality feels heavy.

What is La Casa Azul?

La Casa Azul (The Blue House) in Coyoacán, Mexico City, was Frida’s home, where she was born, lived for much of her life, and died. Today, it is the Frida Kahlo Museum.

What happened to Frida in the 1925 accident?

In 1925, she suffered a severe bus accident that caused multiple injuries. The long recovery and chronic pain that followed shaped her health and profoundly influenced her art.

Why did Frida paint so many self-portraits?

She often painted herself because she spent long periods alone and immobilized, and because her own face and body were the subject she knew best. Her self-portraits act like an emotional diary—identity, pain, desire, pride, and defiance.

Who was Diego Rivera in Frida’s life?

Diego Rivera was a prominent Mexican muralist and Frida’s husband. Their relationship was intense—full of love, admiration, betrayal, and reconciliation—and it left a lasting mark on both their lives and work.

What themes show up most often in her work?

Physical pain, the body, identity, love, loneliness, Mexican heritage (including pre-Hispanic roots), nature, and—at times—stark symbols of blood, hospitals, skulls, and death.

Did Frida really change her birth date?

She was born on July 6, 1907, but she sometimes claimed 1910—the year the Mexican Revolution began—as a symbolic statement of identity and belonging.

What does “The Dream (The Bed)” suggest in her imagery?

It’s a powerful image tied to the fragility of the body and the constant presence of pain and mortality. Frida often turned vulnerability into direct, unforgettable visual language.

How did Frida Kahlo die?

The circumstances of her death have been debated, but her health declined significantly in her last years. What’s certain is that her cultural impact and artistic legacy only grew after her death.

Where can I learn more about Frida in Mexico City?

Start in Coyoacán: the Frida Kahlo Museum (La Casa Azul) and the surrounding neighborhood help place her life and work in context.

Why is Frida still such a powerful symbol today?

Because she spoke with radical honesty about the body, identity, and resilience, her image became an icon, but her paintings remain the most potent part—personal, fearless, and unmistakably hers.