From Pyramids to Magenta Houses: Mexican Architecture

If you ever walk around a Mexican city, it can feel like time travel. On one corner, there’s a massive stone church covered in carvings.

A few blocks away, there’s a bright pink modern house, and somewhere in between, a glass-and-steel library that looks like a sci-fi movie set.

All of that is Mexican architecture, and it tells the story of the country.

Age 1: Ancient cities in stone

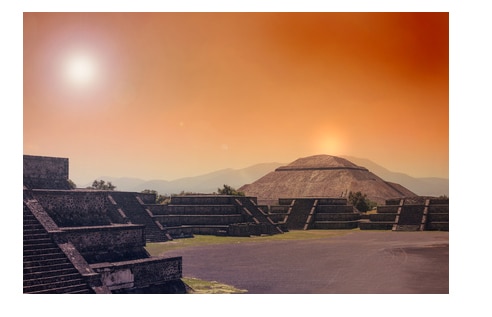

Stunning view to Teotihuacan pyramids

Long before Spain showed up, Mesoamerican civilizations were building huge cities. Places like

Teotihuacan and the Maya sites had:

- Pyramids instead of skyscrapers

- Big plazas for ceremonies

- Buildings lined up with the sun, stars, and cardinal directions

At Teotihuacan, the pyramids use a pattern called talud-tablero: a sloping wall with a flat panel on top,

repeated over and over. It’s innovative engineering and also a strong visual style, and other cities copied it.

These places weren’t just random piles of stone; they were carefully planned

to reflect religious beliefs and political power.

Age 2: Convents, churches, and over-the-top Baroque

After the conquest in the 1500s, Spanish friars rushed to build monasteries and churches, often right on top of old temples.

Early churches look almost like fortresses, with thick walls and big open courtyards for preaching to huge crowds.

By the 1600s and 1700s, Mexico was wealthy, and church architecture went full drama. The style is called Mexican Baroque, a version of Churrigueresque.

Think:

- Facades covered in carvings

- Twisting columns

- Gold leaf, bright tiles, and intense decoration everywhere

If you see a church like Santa Prisca in Taxco, it almost looks like stone lace. Indigenous builders helped create this look, mixing European ideas with local materials, patterns, and colors.

Age 3: A new nation, a new look

In the 1800s, Mexico became independent. The government wanted to look “modern” and “intellectual,”so a lot of official buildings used Neoclassical styles of straight lines, columns, symmetry,like ancient Greece and Rome.

Castillo de Chapultepec

Later, under President Porfirio Díaz, Mexico City tried hard to look like Paris. Wide boulevards, grand theaters,train stations, and fancy houses appeared. But at the same time, some architects began adding

Aztec and other indigenous motifs to show that Mexico wasn’t just a copy of Europe; it had its own roots and culture.

Age 4: Revolution and modernism

After the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920), the focus shifted to the people: schools, hospitals, housing, and universities.

Architects experimented with:

- Art Deco: geometric patterns, stylized decorations

- Functionalism: simple, practical buildings

Ciudad Universitaria UNAM

The UNAM campus in Mexico City, for example, mixes modern buildings with huge murals about Mexican history and identity.

Age 5: Luis Barragán and the magic of color

In the mid-1900s, architect Luis Barragán changed how the world saw Mexican architecture. He used:

- Simple shapes and clean lines

- Bold colors — hot pinks, yellows, deep blues

- Quiet courtyards, pools, and gardens

In houses like Casa Gilardi, walls become giant blocks of color, and light is carefully controlled

so rooms feel calm and almost spiritual. Barragán showed that modern architecture didn’t have to be cold and gray; it could be emotional and deeply tied to Mexican traditions.

Age 6: Mexico today

Modern Mexico keeps mixing old and new. You can find:

- Restored colonial buildings turned into hotels, museums, or cafés

- Landmark projects like Biblioteca Vasconcelos, where metal book stacks seem to float in the air

- Houses and public buildings that use local stone, brick, or rammed earth, and designs that handle earthquakes and heat

How do we honor ancient cultures, deal with colonial history, and live in a globalized, modern world — all at the same time?You don’t need to be an architect to enjoy the answer. Just look around: from pyramids to Baroque churches to pink modern houses,

Mexican architecture is that story written in space, light, and color.

Fast facts about Mexican architecture

- The mystery city: We still don’t know exactly who founded Teotihuacan,

one of the biggest ancient cities in the Americas. When the Aztecs arrived much later, it was already a ruin.

They named it Teotihuacan, usually translated as “the place where gods are made”

or “where men become gods.” - A city on a lake: The historic center of Mexico City is literally built

on top of the old Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, which stood on an island in a lake. - The cathedral is sinking: Mexico City’s cathedral and many downtown buildings are slowly sinking and tilting,

because the old lakebed underneath is soft. Engineers are constantly monitoring and reinforcing them. - Recycled temples: After the conquest, Spanish builders used stones from destroyed Aztec temples

to build churches and government buildings. In some walls you can still spot carved pre-Hispanic blocks hiding in the masonry. - Tiles that tell stories: In places like Puebla, houses and churches are covered in bright

Talavera tiles. Sometimes the patterns are just decorative, but other times they show symbols, dates,

or even little scenes. - Color is serious business: In many colonial towns, there are rules about what colors you can paint house façades

so the streets keep a unified, historic look. That’s why you see whole blocks in coordinated pastels or earthy tones. - Architecture + murals = team effort: On the UNAM campus and other public buildings,

architects and muralists worked together. The walls weren’t just blank surfaces — they were planned as giant canvases

for art about Mexican identity and history. - A house as a World Heritage Site: Luis Barragán’s own house and studio in Mexico City

is so important that it’s been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It’s a regular-sized house, but a global design icon. - Concrete instead of wood: In modern Mexico, most houses and apartment buildings are made with concrete blocks,

brick, and reinforced concrete, while in the United States a lot of single-family homes are still framed mainly in wood.

That’s why many Mexican neighborhoods feel more “solid” and heavy compared to typical U.S. suburbs. - Organic and eco-friendly hillsides: In some “organic” housing projects near Mexico City, inspired by architects

like Javier Senosiain, homes are semi-buried and follow the natural slope of the hill.

Earth and gardens are used as natural insulation, helping control temperature and blend the buildings into the landscape. - Green giants: Some recent Mexican projects focus heavily on sustainability. Big buildings may include gardens,

shaded plazas, and energy-saving systems so they use less water and electricity than a normal skyscraper. - Built for earthquakes: Because much of Mexico is in a seismic zone, architects and engineers design buildings

to sway and flex during quakes. Modern Mexican architecture is not just about looks — it’s also about safety and survival.